By Diane Sierpina

Jhody Polk stood on a stage at NYU Law School, nervously holding a cellphone to her ear. Finally, after several minutes, she broke out in a grin. Colby Lakemper had overcome last minute barriers in a North Carolina prison to call into the Jailhouse Lawyers Conference. He was grateful to share both the successes and horrors of serving as a self-trained legal expert while incarcerated.

Jhody, who in 2018 as a Soros Fellow founded the Jailhouse Lawyers Initiative (JLI) housed at the law school’s Robert and Helen Bernstein Institute for Human Rights, is herself a formerly incarcerated “jailhouse lawyer” – defined as incarcerated individuals who teach themselves the law to advocate for their rights and those of their peers. Since the beginning, she and her mentors at the Bernstein Institute have passionately worked to professionalize the jailhouse lawyer role, create a network that now includes nearly 1,000 jailhouse lawyers located across all 50 states, and cultivate partners on the outside to support these skilled men and women while in prison and upon release back to the community.

This past October, Jhody’s dream came true of hosting an international conference that would bring formerly incarcerated jailhouse lawyers together in NYC with allies from academia, law firms, law schools and other advocacy groups. The purpose was to help raise public awareness of their role as essential members of the American legal ecosystem and their importance to the criminal justice reform movement. By increasing the visibility of jailhouse lawyers, JLI hopes to ensure they have increased access to the best legal education, enhanced legal empowerment skills and trusted relationships with outside organizations, as well as pathways to use their legal skills when they leave prison. Already, some have become paralegals, entered law school (including Jhody), served as interpreters for public defenders or become leaders at law firms and justice reform organizations, offering valuable lived experience. But many more opportunities are needed.

“Creating and living the JLI has been nothing short of divine love and timing,” said Jhody. “We are about to Turn the Lights ON!”

Conference participants used words like “revolutionary,” “transformative” and “life-changing” to describe the three days together. It was hard to imagine the decades many of the attendees had spent in prison who now expressed passion, enthusiasm, optimism, and joy about their new-found global community and prospects for a better future for themselves and those who remain incarcerated. Among more than 100 attendees for the program, at least 40 were jailhouse lawyers from across the US and abroad. JLI raised funds, including from The Tow Foundation, to help bring jailhouse lawyers and allies to the conference, including from Africa, England and the Philippines. They are part of a new international network that JLI helped to create. At least three jailhouse lawyers from Africa supported by an organization called Justice Defenders were refused visas by the US and joined the conference by video. Several Tow Foundation grantees were panelists or attendees, including Hour Children, Common Justice, the Correctional Association, Full Citizens Coalition, Columbia University’s Paralegal Pathways program, and the Tow Youth Justice Institute.

The conference included panels focused on jailhouse lawyers as human rights defenders and modern-day civil rights warriors; women in this role; the importance of law libraries in prison and personal stories of perseverance. There were opportunities for jailhouse lawyers to get professional headshots, attendees to write letters of support to incarcerated members and time for female participants to join a “feminist circle” of support.

During a half day workshop, five currently incarcerated jailhouse lawyers from different states were scheduled to call in to share their experiences. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, last minute barriers placed by prison officials precluded three of them from doing so. Colby, age 48, who has been incarcerated for nearly 20 years in North Carolina, was successful. He described some of the difficulties of helping himself and his peers with their grievances, legal cases and appeals for pardons, parole or clemency from inside prison. There are no copy machines or typewriters available to him and it is against regulations for an incarcerated person to help another one with his case. Like other jailhouse lawyers, Colby has suffered retaliation for his legal expertise and advocacy – including solitary confinement and loss of privileges and property. Some jailhouse lawyers are moved from their cells or even transferred to other prisons for their legal activism. But they keep fighting.

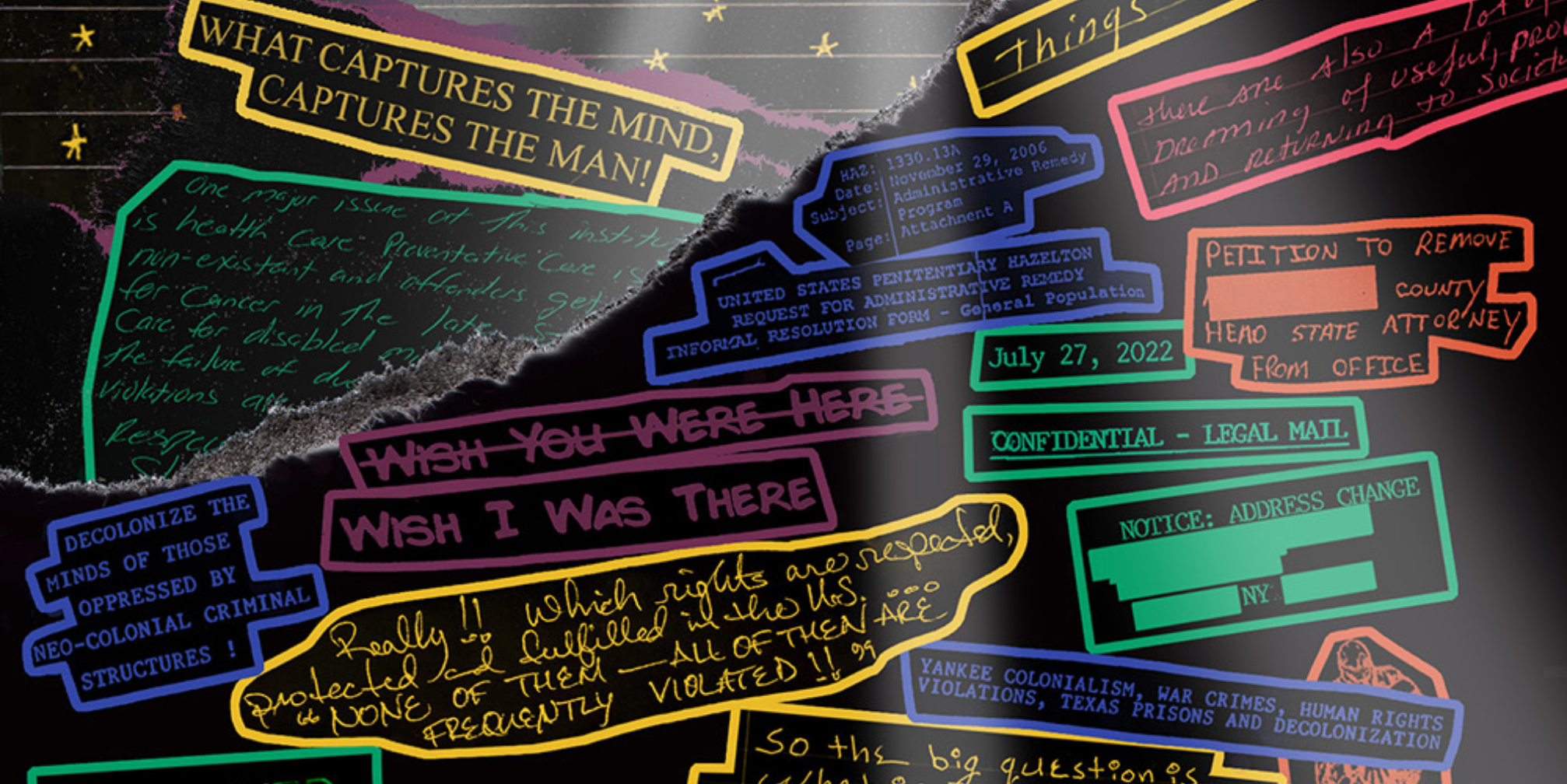

A highlight of the conference was the celebratory launch of Flashlights, the first-of-its-kind digital archive produced in collaboration with Zealous, a Tow Foundation grantee, at a Brooklyn venue that drew 150 revelers. The archive includes 350 letters, artwork and poems from incarcerated jailhouse lawyers and a historical timeline of the jailhouse lawyer movement calling for advancing justice “from the inside out.”

A few days after the event, the hosts were pleased, inspired and planning for 2025. “This wasn’t a conference,” reflected Jhody. “This was a vibe.”